There are a lot of bad investing axioms out there, but probably none so ridiculous and misguided as “Risk Equals Reward”. This is especially true in alternative asset investing where no one pretends that markets are efficient. This belief is so engrained in investors psychology that it has its own Wikipedia page. This pains me deeply. Since I have already written about this broader topic on several occasions, I won’t get into the details regarding the folly of this saying. Instead, I want to discuss a more accurate statement as it relates to risk and return and some observations I have on the current market. With these observations rapidly turning into conviction.

Rather than the ridiculous “Risk Equals Reward”, what we should be saying is investors should demand higher expected returns for taking on additional risk (or uncertainty). Professional alternative asset investors and money allocators understand this and build it into all their return models. Very generically speaking, they will accept returns as low as 12% per year for investment into stabilized assets with strong tenant profiles or as preferred equity; but require expected returns in the high teens for investments that included construction and/or lease up. If they have never worked with a sponsor before they require a more aggressive return split (and therefore in theory higher expected returns). If a sponsor can’t document experience in the type of investment they are raising money for, the return split (and expected returns) will likewise be more aggressive. This understanding of risk is why government bonds have extremely low returns and NNN leases to highly creditworthy tenants (Walgreens/Amazon/etc.) have only slightly higher returns than government debt.

To be able to assign expected returns to particular investment opportunities we need to be able to understand and quantify the risk associated with a particular return. Through understanding the expected returns and the risk associated with obtaining those returns we can then calculate (or at least approximate) the risk adjusted returns of a particular investment opportunity. This in turn allows us to compare opportunities across different risk profiles.

At Altus one of our key product goals is providing better than market risk related returns. Sometimes this means a product like our liquidity fund that returns “only” 4% per year (all as yield) but has high liquidity and very little likelihood of loss of principal. On the other end of the scale we have construction and lease up projects that are anticipated to return in excess of 20% annually (and compounded) but have little liquidity and are subject to risk of changes in the economic or interest rate environment. An opportunity providing a 20% return has to be better than putting money into a 4% return, right? Possibly, but not necessarily. The 20% return is 500% that of the 4% return, so massively higher, without question. Dispassionately, and without taking into account portfolio construction, the question is whether the 20% return also has 500% of the risk of the 4% return. If so, then the two investments are equal on a risk adjusted basis.

Portfolio construction and investment goals makes the comparison of two such investment both easier in some cases and harder in others. For myself, I like to keep a portion of my assets relatively liquid, meaning I want to be able to turn a portion of my assets into cash in 30 – 60 days (I have a smaller amount of truly liquid allocation as well). Even if the 20% return investment had only 200% higher risk than the 4% return there is no situation where it makes sense to invest this allocation of my assets into the higher return opportunity. Conversely, I have goals for myself and my family for which a 4% return will never achieve. Therefore, it makes complete sense to take the higher risk associated with the higher return opportunity for a portion of my assets because the higher expected returns are what is needed to achieve these goals. Taken a step further, if I allocate investment across several of the higher rate opportunities it protects me from loss on one of the investments while still generating generally higher returns.

There is nothing insightful or cutting edge in these thoughts. It is pretty basic investing 101.

Applying this thinking to the current real estate low interest rate and low cap rate environment creates dissidence to historical ways of thinking, even within Altus’s most fundamental investment guidelines. We have 12 individual investment philosophies that make up our summary philosophy. Eight of the twelve outline how we make and structure investments more broadly (alignment, values, etc.). Of the remaining four points that speak specifically to investment characteristics, three of them talk about cash flow, interchangeability, and investing at a favorable basis to replacement cost.

Those three specific philosophies have been key guiding principals throughout the past decade and have led to strong returns for our investors (especially when viewed on a risk adjusted return basis).

The last guideline listed in our philosophy reads, “There are certain circumstances when we deviate from “standard” investment guidelines and capitalize on entrepreneurial opportunities. When underwriting, we identify what is different about an opportunity and ensure that we are willing to take on any additional risk associated with the investment.” In other words, this guideline says we are able to throw out the three previously mentioned guidelines if we do it consciously and it makes sense to do so. The only way it would make sense to do so is if the expected risk adjusted returns are outsized versus returns available elsewhere in the market.

More and more over the past several months we have been making the conscious decision to take on opportunities that fall into this last guideline. With the standard of internal approval to pursue such opportunities considerably higher than our more historically common opportunities, what is the change that is causing this happen? Is it an internal acceptance of higher risk ventures? Is it something in the market?

As readers know, interest rates are at historic lows. This, along with immense amounts of liquidity in the investment markets has caused cap rates to continue to compress, and with it, yields and internal rates of returns buyers/investors are willing to accept. With this we have seen a sizeable increase in the aggressiveness of underwriting assumptions, assumptions we just can’t justify in our own models. Will cap rates remain this low for the coming five to ten years? Will rents increase at 4, 5, or 6% a year for the coming five years? Can an operator really operate a property at 97% economic occupancy? Etc.

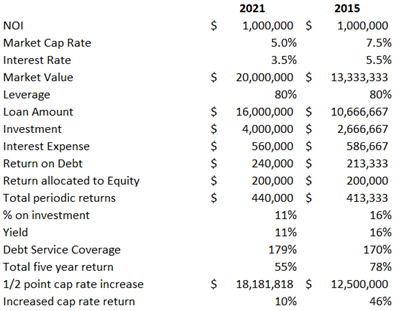

To properly understand the impact on an investment lets compare the same property performance between the current market and an approximation of where the market was 6 – 8 years ago. I am taking some liberties for the sake of illustration and simplicity and will ignore transaction costs and the sponsor/investor allocations within this investment level analysis. There are a lot of numbers in the illustration below; but stay with me. If you look at the debt service coverage ratio an argument could be made that today’s purchase would be (very slightly) safer than the same purchase six years ago. However, a closer look shows that the returns six years ago were substantially higher than they are today while also being less susceptible to an increase in market cap rates.

What the above example doesn’t contemplate is that these are interest only numbers. Six years ago a full-term interest only term was nearly unheard of. Today sponsors are often pushing for as many years of interest only as they can find, even to a full ten-year interest only loan in some circumstances. This helps increase IRRs (a dollar today is worth more than a dollar next year) but leaves investors highly exposed to changes in cap rates over the term of the loan. For instance, using the above 2021 example, if cap rates were to increase 1% instead of the .5% shown in the example (not at all unheard of over 5 years) the investment equity is basically wiped out.

But wait, there is more. The last 18 months have shown us there is risk in the real estate markets that no one, no one, had previously quantified. No one could have imagined that state governments would shut down economies to the point where retailers could no longer exist and office users would not be able to use expensive space in metro centers, and therefore not pay their rent. No one could have imagined the CDC would institute an eviction moratorium that would allow non-paying residential residents to stay in units months upon months without paying, not just reducing revenue for the property owner but forcing owners to pay operating expenses for units for which they had no hope of collecting rent – a double penalty versus just having an empty unit.

This leaves us with a twofold issue. Lower returns actually increase the likelihood of loss and therefore result in considerably lower risk adjusted returns. And, at the same time, the true risk of the investment has increased, further reducing risk adjusted returns.

Meanwhile, risks on more opportunistic opportunities has largely remained the same, or even been reduced. There is so much money currently chasing loans that leverage on opportunistic deals is at previously unheard of levels and at interest rates that greatly reduce carrying costs of such opportunities. At the same time, this debt can be negotiated to be non-recourse. With non-recourse debt, the most that can be lost on an investment is 100% of the initial investment, which is the same potential loss that existed at the base year 6 years ago as used in the comparison above. And, with the higher leverage options, losing 100% of an investment is a smaller loss than it would have been previously. Additionally, the chance of loss now versus 6 years ago is arguably lower due to more favorable debt terms available that provide a longer runway for an opportunistic opportunity to reach its potential.

So where does that leave us?

- Returns on stabilized yield producing investments are down – dramatically.

- The very factors that are creating the decrease in returns are actually increasing the risk associated with those returns.

- Reduced returns and increased risk results in considerably lower risk adjusted returns.

- Meanwhile, opportunistic/entrepreneurial opportunities have generally not seen as large of a return impact.

- These opportunistic opportunities could arguably be considered to have less risk than previously.

- Opportunistic opportunities therefore have not had an impact to their risk adjusted returns.

- When taken in comparison, stabilized investments have become far less attractive on a risk adjusted return basis versus opportunistic opportunities.

When viewed through this analysis it makes a lot of sense to me as to why Altus has been gravitating more towards opportunistic opportunities. If, by comparison, opportunistic opportunities have better risk adjusted returns then we should be making that move.

I must caveat however, that this analysis is very general in nature, while real estate itself is not. Not all yield producing investments have worse risk/return profiles and not all opportunistic opportunities are comparatively better places to invest. Each new investment and opportunity needs to be understood and evaluated on its own merit.

Happy Investing.